On The Arrival of Qi

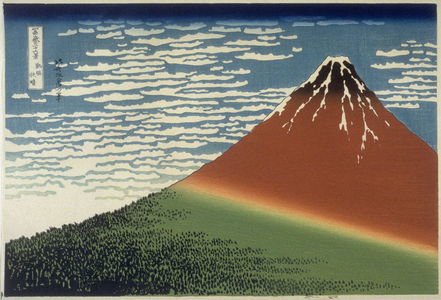

Hokusai. Gaifu Kaisei, from 36 Views of Fuji. 18th-19th century.

I.

In the practice of acupuncture, the purpose of needle insertion in an appropriate point is to restore the flow of life-energy (or qi). This purpose is divided into two possible actions: tonification (when qi is deficient) and sedation (when qi is excessive). These two actions translate into distinct needle techniques, the details of which depend on the tradition of practice.

According to the classics, tonification is achieved by inserting the needle slowly, at a 10-15 degree angle in the direction of the meridian flow, synchronized with the patient’s exhalation. Once the arrival of qi is felt, the needle is swiftly removed as the patient inhales, and the “hole” is closed with the thumb (to prevent the “leaking” of qi). In order to facilitate the arrival of qi, the practitioner may utilize any number of techniques, most commonly a rotation of the needle clockwise or rapidly back and forth between the thumb and index finger. In the Worsley Five-Element tradition, tonification is achieved via a clockwise 180º rotation of the needle. In other schools, the needle rotation may be a full 360º or involve a variety of needling actions.

Sedation is achieved by inserting the needle quickly, against the meridian flow, and with the patient’s inhalation. The needle is retained up to 30 minutes and then removed slowly with the patient’s exhalation, without closing the “hole”. While the needle is retained, the practitioner may rotate the needle counter-clockwise to effect sedation.

An important corollary to the goal of tonification is the issue of pain upon needle insertion. According to Kodo Fukushima, one of the fathers of Japanese Meridian Therapy, pain upon needle insertion is inherently dispersing rather than tonifying. This seems quite logical, as pain can be observed as a momentary contraction of energy, a naturally reducing movement. For this reason, practitioners of the Japanese tradition place much emphasis on painless needle insertion and subtle needle techniques. This is accomplished through a gestalt of various factors including the use of thinner needles, superficial rather than deep insertion (or even non-insertive approaches), and the practitioner’s ability to needle with their energy and attention centered in the hara.

In the Worsley five-element tradition, tonification is the general approach, as the etiology of the “causative factor” ( or “C.F.”) is a paradigm of root-deficiency involving a single phase-element. In Japanese Meridian Therapy, the root-deficiency is conceived as a pattern involving the two most deficient yin meridians in a mother-child relationship. These two yin organs are tonified while any excess in yang organs is sedated (although the sedation of yang organs is not always applied, per Shudo Denmei’s approach).

II.

This brings us to the question of qi sensation as a measure of efficacy. In the context of tonification technique, the practitioner waits for the “arrival of qi” before removing the needle. In Chinese traditions, this is described as de qi, and corresponds to a sensation of the needle becoming heavier as if being pulled down by a fish on a hook or any number of similar sensations. This is also felt by the patient commonly as a dull aching sensation of varying intensity. In some cases, the sensation may feel more “electric”, tingling, or the site of insertion may become itchy. There is no “right” or “wrong” sensation in this regard, the point being that the practitioner and the patient both feel the arrival of qi. We can note that in the Chinese tradition, thicker needles with deeper insertion techniques are employed to induce a moderate to strong degree of needle sensation in the patient.

However, in Classical Japanese Acupuncture, Shudo Denmei offers a distinction between the “arrival of qi” and needle sensation. He refers to the arrival of qi as ki itaru and quotes a passage from the Ling Shu:

The essence of acupuncture is that the effect comes with the arrival of qi. The sign of this is like the wind blowing the clouds away. It becomes clear and bright as if looking into the blue sky. This means the purpose of acupuncture has been fulfilled.

Denmei comments on this passage, distinguishing between the arrival of qi (ki itaru) and needle sensation (tokki):

When the seasoned practitioner feels a sudden change at the site of needle insertion which indicates that the needling is having an effect, this is known as the arrival of Qi. These days we hear a lot about a similar term known as obtaining Qi (tokki/dé qi). The literal meaning of the terms arrival of Qi and obtaining Qi seem to differ very little, but there is actually a great difference”.

Denmei quotes the Shanghai College of Traditional Chinese Medicine which states:

Obtaining Qi is generally known as needle sensation (zhēn gan).

While most practitioners regard the “arrival of qi” to be synonymous to “de qi”, Denmei is pointing out a critical nuance. To support his point, he quotes Sorei Yanagiya, a modern master who contributed significantly to the revival of classical acupuncture in the 20th century:

In contrast to obtaining Qi, which is felt by the patient, the arrival of Qi is something that the practitioner feels. The extremely delicate changes that an experienced practitioner learns to sense are known as needle subtleness (shin myo/zhēn miào).

Denmei concludes his argument by quoting Sugiyama Waichi, a legendary figure considered the father of Japanese acupuncture:

When there is sinking, heaviness, dullness, tightness, and fullness after the needle is inserted, and it feels as if a fish has swallowed the hook, and there is movement which seems sinking at one moment and floating at another, it means that the Qi has come . . . When there is floating, lightness, slipperiness, emptiness, and smoothness, and it feels like being alone in a quiet room where there is stillness with no sound to be heard, it means that the Qi has yet to arrive.

Fundamental to the Japanese approach is the notion that greater stimulus disperses Qi where lesser stimulus strengthens Qi. This is the essential difference between the Japanese sensitivity to the “arrival of Qi” vs. the Chinese approach of “obtaining Qi”. In the Japanese approach, the patient may not feel anything at all upon needle insertion or the patient may feel a pleasant energetic sensation of warmth and flow. However, Denmei is clear that there is no requirement for the patient to feel anything in order to confirm the arrival of Qi, rather it is the practitioner who senses this subtlety.

The “arrival of Qi” vs the “obtaining of Qi” reflect different philosophical orientations. The “arrival of Qi” pairs with the understanding that a minimal stimulus, more akin to a “suggestion”, is all that is needed for the body to self-correct. The “obtaining of Qi” pairs with the understanding that a maximal stimulus accomplishes for the body what it is not presently doing, thereby repairing the present insufficiency. The former holds a view that the body heals itself when allowed to do so (or when gently encouraged, or reminded, of its natural order). The latter holds a view that the body heals through proper intervention, where what is missing is called forth and made to happen where it previously was not. In the former, the source of efficacy is the body itself, whereas in the latter, the source of efficacy is either directly or indirectly implied in the practitioner.

The Worsley tradition appears to straddle the line between Japanese and Chinese needling approaches, even while its philosophical orientation seems largely in agreement with the Japanese approach. Eckman details this in the following recounting of Worsley’s nickname, “The Feather”:

LA [Worsley Five-Element] employs a considerably different needle technique than is typical of TCM. The goal of TCM acupuncture is for the patient to experience a sensation called “de Qi,” which can be perceived as heaviness, soreness, aching or distention. In LA on the other hand, it is the practitioner who feels the “Qi” through the handle of the needle, and it is not considered necessary for the patient to feel anything at all. Worsley’s clinical nickname, “the Feather,” undoubtedly refers to this delicacy of touch. This aspect of LA needle technique is shared with the majority of Japanese styles of practice, to which Worsley was exposed.

However, Fratkin, a practitioner of Japanese styles, implies the approach of Worsley five-element practitioners is closer to “obtaining Qi” via needle sensation rather than the arrival of Qi described by the Japanese. He believes that Worsley’s needle technique is inspired by the teacher, Wu Wei Ping, who taught Chinese needle technique. Eckman’s comments seem to indicate otherwise, although approaches seem to vary among practitioners of Worsley’s style. Some practitioners consistently elicit a strong needle sensation in their patients and I have heard patients refer to five-element style as “the kind of acupuncture that hurts”. Granted, Worsley’s style uses a free-handle needle technique for maximum control and sensitivity, an approach that requires considerable skill to execute painlessly. I have certainly seen some practitioners who look very specifically for the patient to experience the needle sensation as a confirmation that the needling has been accurate and effective. Despite these differences in practice, the evidence of Worsley’s own history and practice point to a more Japanese-inspired needle technique than Chinese, if we are to rely on Eckman’s compelling accounts.

III.

We can also consider the arrival of Qi, apart from needle technique, as a dimensional event. In acupuncture, we are working with the subtle form of Qi that circulates in the twelve meridians of the body. These subtle structures have physical correlates but the meridians are in no way identical or reducible to a physical structure. Rather, meridian exist as the pathways of energetic circulation, a process within and behind the physical dimension, the interface between everything. The pursuit of a physical Qi sensation––either under the needling hand or in the patient’s experience––is the obtaining of Qi on a more physical level. The pursuit of an energetic sensation––under the needling hand and quietly noticed by some patients––is the arrival of Qi on an energetic level. Beyond this, once can also sense the arrival of Qi at the level of the Spirit, when it simply happens in place and in silence. This is sensing at the root, at the origin of all happening.

The arrival of Qi is not limited to the sphere of the patient’s body. In my experience, the arrival of Qi is mostly felt in the room itself, as a change in the energetic atmosphere of the treatment space. There is a felt sense of change, a kind of re-vitalization. I find the arrival of Qi is more of a spontaneous happening than an induced event, like the falling of rain after a prayer. Further, the arrival of Qi is not restricted to the practice of needling acupuncture—it must equally apply to moxibustion and purely energetic modes of healing (even at a distance).

Before studying acupuncture, I learned a form of medical Qigong therapy, described by my teachers as “Wuji Qigong”. The fundamental practice was meditative in nature and there was no discernible technique of treatment. Rather, the practice focused on the practitioner’s energetic cultivation and the natural ability to be energetically present with the patient as the treatment itself. Treatments were often done at a distance and mostly without any direct physical contact with the patient. In some sense, I found treatments were even more effective a distance. As a visual person, I always saw the patient in my mind’s eye while treating them. At some point, in the first few minutes of treatment, I could feel when I had made the connection with the patient. It was a subtle but obvious feeling of connectedness and energetic flow, a perceptible shift in my own body and mind. This is the arrival of Qi—the resonance between the patient and practitioner, Heaven and Earth, macrocosm and microcosm, Spirit and form.

More and more, I find acupuncture (and the healing arts in general) to be a sacred practice. This means the practitioner is ideally a priest, not merely a master of technique. Only then can treatment become an invocation, a prayer, a meditation that re-flowers every juncture of unity.

References

[1] Japanese Classical Acupuncture: Introduction To Meridian Therapy by Shudo Denmei.

[2] Classical Five-Element Acupuncture, Vol II: Traditional Diagnosis by J.R. and J.B. Worsley.

[3] In The Footsteps of the Yellow Emperor by Peter Eckman, p. 468.